I travelled 16 kilometres south of Westport recently into the hill country of Drummin to meet one of the county’s world champions. Along a road lined with meadowsweet, heather and vetch I journeyed to the home of James Hopkins, a sheep farmer and fastest man with a hand shears at the world shearing finals last year.

We had met earlier in the summer, at Kepak Shearfest, a national competition organised by the Irish Sheep Shearers Association at Mountbellew Mart on a sunny weekend in early June.

There Hopkins sheared his way to the all Ireland and All Nations titles in the hand shearing competition, known in the trade as the blades category. At 23, he was already a world champion first in the All-Nations blades Open competition held during the world sheep shearing final in Scotland. Competitive shearers compete at novice, junior, intermediate, senior and open levels.

Hopkins made his foray into competitive shearing as an eleven-year-old at a Drummin show, in 2011. “Dad showed us how to shear. I was maybe eight years old. We weren’t strong enough to hold a sheep, but he’d start, he’d open the sheep’s fleece and we’d take over and finish.”

In 2014 James came third – his brother Martin was first – in the U-18 final at the Connacht Spring Show in Ballinrobe. Each competitor shore two sheep each. “At the local shows there was no pressure. That started encouraging us to compete,” he recalls as we sit in the Hopkins family homestead, a handsome bungalow under an imposing hill of granite rock pock-marked with vegetation.

Since that day in Ballinrobe a decade ago Hopkins has been to France twice, competing in the world championship in 2019.

He will have five competitions next year to gather the points needed to make the Irish national team for the 2026 world sheep shearing finals in New Zealand.

Hopkins wants to defend his hand shears title but Hopkins also wants to go electric. Next year he will also compete in the machine shearing, seeking to compete in a very competitive discipline requiring new depths of endurance and accuracy.

The honour call from annual national electric shearing competitions run by the Sheepshearers Association of Ireland has been dominated by men from counties populated by large sheep herds – Donegal and Galway are well represented, Kerry too. Mayo is home to multiple-time national champion (dethroned this year) Ivan Scott, a Donegal sheep farmer now living in Ballinrobe.

The three Hopkins brothers are today known globally in the world of competitive shearing. Peter Herrity, who lives ten minutes from Hopkins’ door, is another star. He came fourth in the blade section at this year’s national finals in Mountbellew.

Shearing is an ultra-competitive sport, but one of camaraderie among men (women also compete) who in many cases come from similar ovine herding traditions of hill lands where only sheep thrive. Hopkins talks of the “great respect” between the competitors.

“I was only 17 when I started but I was shown great respect by the men in their 30s and 40s, they were giving me advice.”

In Mountbellew I watch as the Hopkins brothers sit in the spectators area, James with a tool box under the plastic chair full of his shearing gear. Then it’s his turn to compete and the man on the tannoy offers some biographical details on the Drummin man, still one of the youngest competitors in the field. The announcer works the crowd into an excited roar for their respective shearers. With a sheep’s head through the legs and crouched over Hopkins clips away with a practised, accurate intensity. “It’s fast and furious!” shouts the man on the tannoy as the shearers grab their first sheep and set to work.

The Hopkins brothers’ emergence has brought vitality to an ancient skill that’s also a subculture and a cultural tradition in danger of decline. Shearing competitions were a feature of life in west Mayo, in towns like Leenane and Louisburg with large flocks of Mayo black face sheep who on August days prowl amid the holly and the willow, among the few trees tough enough to grow in abundance on this elevated landscape which stretches down to Leenane and Galway.

But it’s been some time since there was a county shearing competition. There are photos online from Darly’s pub in Cushlough, host to the Cushlough sheep show which often features a shearing competition. There’s also footage of a gap-toothed Scotsman, Tom Wilson, surrounded by onlookers as he towers over a sheep in Ballinrobe in 1987, all the while telling RTE reporter Jim Fahey about the international sheep shearing competition circuit.

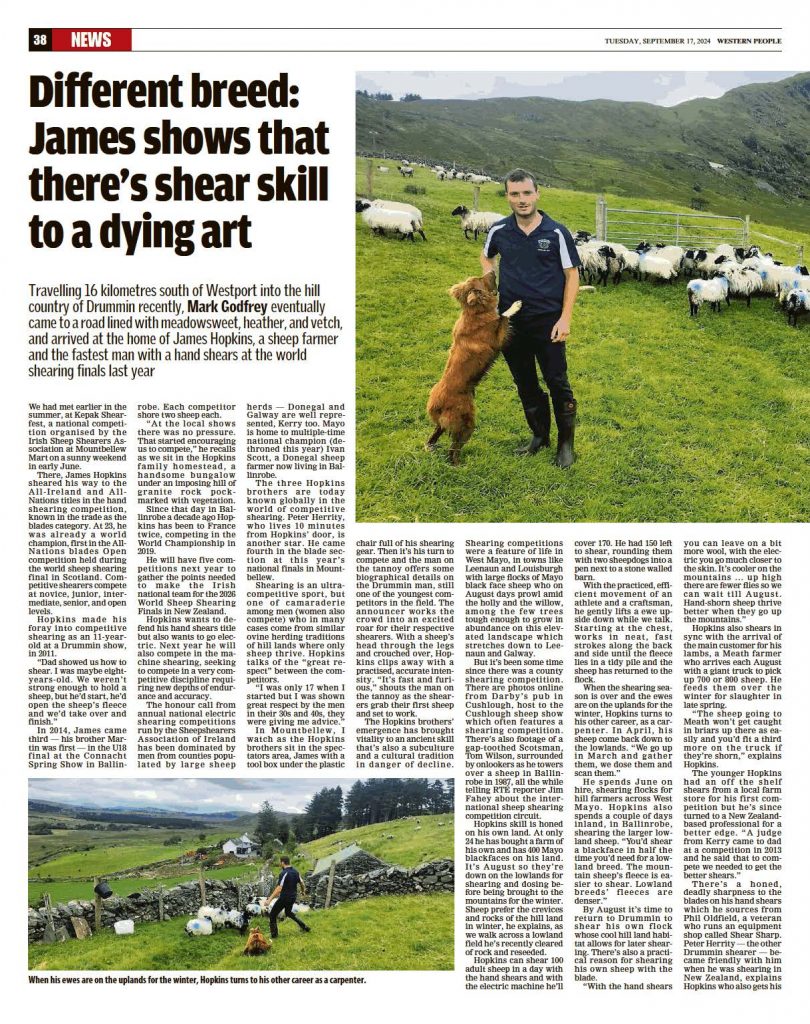

Hopkins skill is honed on his own land. At only 24 he has bought a farm of his own and has 400 Mayo blackfaces on his land. It’s August so they’re down on the lowlands for shearing and dosing before being brought to the mountains for the winter. Sheep prefer the crevices and rocks of the hill land in winter, he explains as we walk across a lowland field he’s recently cleared of rock and reseeded.

Hopkins can shear 100 adult sheep in a day with the hand shears and with the electric machine he’ll cover 170. He had 150 left to shear, rounding them with two sheepdogs into a pen next to a stone walled barn.

With the practised, efficient movement of an athlete and a craftsman he gently lifts a ewe upside down while we talk. Starting at the chest, works in neat, fast strokes along the back and side until the fleece lies in a tidy pile and the sheep has returned to the flock.

When the shearing season is over and the ewes are on the uplands for the winter Hopkins turns to his other career, as a carpenter. In April his sheep come back down to the low lands. “We go up in March and gather them, we dose them and scan them.” He spends June on hire, shearing flocks for hill farmers across west Mayo. Hopkins also spends a couple of days inland, in Ballinrobe, shearing the larger lowland sheep. “You’d shear a blackface in half the time you’d need for a lowland breed. The mountain sheep’s fleece is easier to shear. Lowland breeds’ fleeces are denser.”

By August it’s time to return to Drummin to shear his own flock whose cool hilland habitat allows for later shearing. There’s also a practical reason for shearing his own sheep with the blade: “With the hand shears you can leave on a bit more wool, with the electric you go much closer to the skin. It’s cooler on the mountains… up high there are fewer flies so we can wait till August. Hand-shorn sheep thrive better when they go up the mountains.”

Hopkins also shears in synch with the arrival of the main customer for his lambs, a Meath farmer who arrives each August with a giant truck to pick up 700 or 800 sheep. He feeds them over the winter for slaughter in late spring. “The sheep going to Meath won’t get caught in briars up there as easily and you’d fit a third more on the truck if they’re shorn,” explains Hopkins.

The younger Hopkins had an off the shelf shears from a local farm store for his first competition but he’s since turned to a New Zealand based professional for a better edge. “A judge from Kerry came to dad at a competition in 2013 and he said that to compete we needed to get the better shears.”

There’s a honed, deadly sharpness to the blades on his hand shears which he sources from Phil Oldfield, a veteran who runs an equipment shop called Shear Sharp. Peter Herrity – the other Drummin shearer – became friendly with him when he was shearing in New Zealand, explains Hopkins who also gets his sharpening tools and techniques from Oldfield. “He comes over to Ireland giving us demonstrations.”

Hopkins’ shears are made by Burgon & Ball in Sheffield, one of the few great pre-war companies to survive the recent near demise of the British steel industry. “You can open them up, so you get a bigger cut,” says Hopkins, passing me the shears. “They’re also more ergonomic. There’s less stress on the arm.”

Hopkins is self-taught but did two courses recently on shearing with machines, organised by the Irish Sheep Shearers Association. He competed in the machine at a recent competition in county Kerry, coming fourth in the junior category. It was his second time on the electric grade, after a tournament in Donegal in 2023.

“It’s more competitive,” he explains of the electric grade, meaning it’s a more crowded field. Many of those on the electric have never shorn with the blades. Hopkins hopes his hand shearing skills will transfer well to the machine.

When he’s home shearing his own sheep his focus is not on speed but on neatness.

“A lot of people try to be very quick. “Getting the two together is the key. You have to be quick but you have to be clean and neat.”

Judges mark competitors down for leaving too much wool on the flesh. At the competition in Mountbellew judges in their white coats imprinted with a red Farmers Journal logo, stand over the shearer mid-competition, looking for cuts and grazes.

Behind the stage there’s a more careful examination of the shorn sheep. The fastest shearer won’t necessarily win. Competitors also get to view the sheep they’ll shear beforehand: “if you see one that’s very dirty you could get her changed,” explains Hopkins who wants to save time on sharpening his shears. “You can shear five or six sheep without sharpening, unless you hit some sand or dirt in the fleece.”

It’s not a coincidence that the elite shearers in Mountbellew are also the more athletic. “Throughout the day you can see the fitter person is able to shear more consistently and more sheep,” says Hopkins.

The tournament in Mountbellew was a two-day test of endurance and skill. In the crowded electric section shearers compete through three or four rounds over two days to make a final. In the final round of the elite Open competition shearers have a maximum 20 minutes to shear 20 sheep.

Under the corrugated sheeting of the mart in Mountbellew spectators in the rows of plastic chairs follow the action up on a wooden platform straight ahead. Commentators take turn on the tannoy to describe the action. Some competitors’ names sound like they’ve rolled off the Welsh hills: Richard Jones and Gethin Lewis. At stand four Jones, a world champion, runs his shearing machine in round strokes as he opens up the fleece.

Walking around the competition grounds in between heats are men with farmers’ tans in sleeveless shirts bearing a sponsor’s name, expensive-looking electric shears in one hand and the metal bars that secure them safely to a power source in another.

There’s full tans too: the men back from a season shearing in Australia. And then there’s men from up north like Stanley Allingham, from Fermanagh, who shears seven sheep in six and a half minutes. Kerryman Denis O’Sullivan won his heat in the Open competition. But it’s Jones who wins the ultimate prize, leaving the Ballinrobe-based Ivan Scott in second.

Hopkins approaches shearing as a time-watched sport as much as a trade where neatness is demanded. But global trade and economics have completely upended the economics of the shears within Hopkins own lifetime. In Drummin he holds up the fleece he’s shorn while talking to me. It weighs little over a kilo. So it’s worth five cents, the current global average farmgate price for wool and a fraction of the price paid even in 2011.

Thirty years ago wool was the most lucrative earner a sheep farmer had, Hopkins offers. “A man comes to collect it and weigh it. Some fleeces don’t weigh much more than a kilo so that’s it. Five cents a kilo, five cents a fleece.”

A glut of new petrochemical processing capacity in Asia in recent decades has brought new supply lines of cheap synthetic fabrics, like polyester, eliminating the demand for wool.

It’s no coincidence that the Mountbellew national finals are sponsored by a meat (not a wool) company, whose executives in uniform brown shoes and blue suit trousers seek to engage sheep farmers in a hospitality tent at the site. There have been efforts to find alternative uses and markets for wool, or at least to preserve the skills of an ancient industry. A team of ladies wearing polo shirts that say ‘Ulster Wool’ take the freshly shorn wool from the wooden platform to toss and shape it effortlessly into wrapped bundles. Wool handling too is a skill and the Ulster Wool company sponsors a competition in Mountbellew.

Shorn of a lucrative income source, sheep farming becomes less appealing, even in west Mayo where the blackface thrives in land inhospitable for cattle, who are conspicuous by their absence around Drummin. “Maybe four or five farmers around here with cattle, that’s all. The land is too wet, they’d cut it up. And the winter would be too long, they’d be inside from September to May, that’s a very long winter.”

An absence of successors means that as farmers get older they’re cutting sheep numbers, explains Hopkins whose youth and 400 ewes make him an outlier of sorts in the hill country connecting the prosperous towns of Westport and Clifden.

“But there’s still a few people around here with five or six hundred sheep,” he adds, hopefully. And there’s still enough sheep in the country to draw Australian shearers each summer to Ireland for the shearing season. Hopkins knows three who’ve made the journey.

But there’s also Irish and British shearers making the return journey, for a winter shearing in the Antipodean summer. and it shows in the shearing. “They have work lined up with contractors for a few months between November and March,” explains Hopkins. “You see a big change when they come back.”

It sounds like he’d like to compete in their league, and he will in 2026 if he travels to New Zealand for the world finals. He’ll potentially shear in both the hand and the electric shearing categories in that competition. But in the meantime he’ll be a carpenter for the winter, until March comes and he goes up the mountains to gather his sheep. Then, after lambing, a new shearing season won’t be far off.

Article appeared in the September 17, 2024 edition of the Western People.